Joe is a local historian in Piedmont, South Carolina working on his PhD in textile history. Prior to his move to South Carolina, he worked in the Smithsonian archives in historical research.

Paternalism and the Piedmont YWCA

October 16th, 2022

Piedmont Manufacturing Company started spinning its spindles in 1876 after construction of the first mill building by owner Henry Hammett. Soon after completion of the first mill building, Hammett moved on to build more than just mill buildings in Piedmont, including the mill village itself for the employees working in Piedmont’s mills. Overtime mill leaders would add to Piedmont’s landscape, numerous buildings housed and served the village and its inhabitants, including the building that would house the Young Women’s Christian Association(YWCA).

In 1879 the Union Church was built, but after 1895, congregations no longer used the church. By 1908, with a recognized need to house young single mill workers, mill leaders had the Union Church remodeled,to become the first YWCA in South Carolina. Two women were hired to look after the welfare of the young women who lived on the second floor of the YWCA, keeping a watchful eye on the young residents.

On the lower floor of the building, two large rooms were available for the girls to use, the sitting room with piano and a library. The YWCA held social events, dances, and entertainment as well as educational activities in the form ofpresentationsand classes.Many of the classes taught at the YWCA were on domestic skills such as sewing, nutrition, and cooking.[1]While this may seem an extraordinaryeffort in management of young female workers, this form of paternalistic management had deep roots in textile mill industry dating back to the early 19th century.

In 1820, Boston investors established what would be a model textile mill community in Lowell, Massachusetts. This also happened to be the first factory in the United States. Learning lessons from England where the British factory system represented extreme exploitation of employees and inhumane work conditions, the investors envisioned something different. Instead of using child labor as in England for its factory, Lowell Mills employed local girls from the surrounding farms. With a paternalistic mindset, the girls were housed in company boarding houses under the supervision of a matriarch.

Mill girls not only worked in the mills but were encouraged to attend educational lectures hosted by the mill, as well as utilize the company library. Whether working or on their off time, the girls were closely watched monitoring their behavior. They were prohibited from consuming alcohol, playing cards and gambling. Their boarding house matron supervised their conduct ensuring the girls maintained proper moral behavior[2].

Despite what sounds oppressive, the mills girls were paid well for their labor, two to three times the wages of young women who did not work in the mill. The owners found this paternalistic oversight of the mill girls not only important for the welfare of the girls, but also forthe success of the mill factory itself. Paternalistic traditions played an important role in the development of not only Lowell’s Mills, but also in the future development of Piedmont’s YWCA nearly 100 years later. And yes, women mill workers were the first factory workers in America.

Author: Joe Hursey, former Historian/Archivist at the Smithsonian Institution; is currently a volunteer for the Piedmont Historical Preservation Society

For more information on the history of Piedmont Manufacturing, the history of textiles in the upstate and in our area, or accessing our research collections, please visit Piedmont Historical Preservation Society – Discover Piedmont

You can also contact us at our Facebook page Piedmont Historical Preservation Society | Facebook

Be sure to catch more on mill history on TV Channel 4, Chronicle: Remaking the Mills

[1]Peden, Anne. History of the YWCA. Piedmont Historical Preservation Society, August 2022.

[2] Davidson, James, et al. Experiencing History: Interpreting America’s Past: Volume 1: To 1877, Ninth Edition. McGraw Hill, 2019, pp 232-233.

Domination of the Southern Textile Industry

In 1962, Greenville, South Carolina claimed the title “Textile Center of the World”, after they opened their newly built Greenville-Spartanburg International airport. Now were they actually the textile center of the world, this depends on who you ask and how it is measured. Regardless of how it was determined, by the mid-20th century southern states produced more textiles than anywhere else in the world.

Despite Greenville’s claims, the south did not always dominate the national textile market. In 1789 Samuel Slater a British skilled textile worker arrived in Pawtucket, Rhode Island and built the first textile mill in the United States. He founded his mill alongside Pawtucket’s Blackstone River that provided waterpower for his new industry. But once his mill began operations, it would not take long before other New England entrepreneurs realized the financial windfall from investment in textile mills; mills immediately began springing up all over northeastern states, making New England mills the dominate American textile producers.

While New England mills led the nation in textile production, they had to depend on southern states to supply the raw cotton for their industry. New England textile factories made money hand-over-fist reaping large profits, while southern cotton farmers saw little profits from the industry. It would not take long for southern businessmen to view their position as nothing more than a “colonial economy” for northern industries. Once cotton was turned into textile it was worth three times the price that was paid for the raw product. Then it was resold back to the south. Many southern businessmen began questioning, “why not build our own mills and keep the money for ourselves?”

There were a handful of southern textile mills I the early 19th-century, but these were normally retrofitted factories, operating with out-of-date machinery that had been discarded by northern mills when they updated their machinery. Due to the lack of modern machinery, southern mills normally produced low-grade basic textiles such as yarn and wool for sale to local markets.

By 1845, southern business leaders believed that if the southern states were to ever stand equally as their northern neighbors and break away from the position of a “colonial economy”, they needed to develop their own competitive industries, and some saw textiles as the path forward. One of these businessmen was William Gregg, who in 1845 published a series of essays arguing for a south built upon textiles mills. Gregg stated that the south had many advantages over the north as textile producers. First, southern textile mills incurred reduced freight costs associated with transportation; as well as increased sources for waterpower; lower or no taxation on industry; and lastly and the most important factor, cheap and abundant labor.[2] While the south had these advantages, initially it lagged in its development of its textile industry.

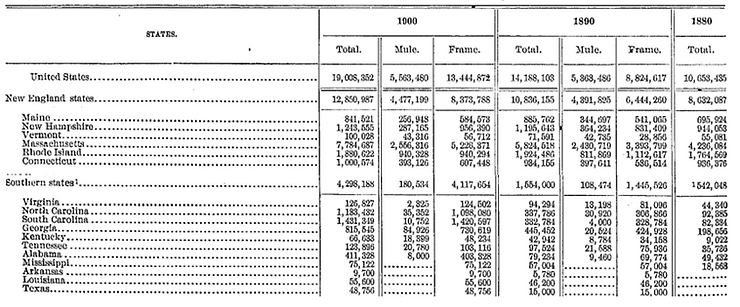

Although southern industrialist invested heavily into development of their textile industries, just to say that they eventually dominated U.S. production of the textile market is not enough. Statistical data presented here will demonstrate this growth and development of southern textile industries. This statistical data originates from 19th-century trade publications and U.S. Censuses. These publications provided invaluable numerical information that revealed postbellum production capabilities of the New England mills compared to Southern mills starting from 1860 running until 1900. There are numerous other statistical sources produced during the postbellum period, but the specific trade publications and U.S. Censuses records used for this research appear to be the most reliable sources. Also, in an attempt to present a consistent comparison of size, production capacity and growth of textile mills, the number of “spindles” in operation are used and a measurement. While this seems as an unusual method of industrial measurement, spindle count is commonly used as a determinant in tracking mill size, production capacity and growth. Table 1 below serves as an established base number of New England and Southern mills production capability starting at 860 at the beginning of the postbellum period.

TABLE 1

Table 1 illustrates that in 1860 southern textile mills controlled 5.8% of U.S. textile production, while New England mills controlled 73.9%. But a southern textile revolution began in the early 1870’s that led to the construction of hundreds textile mills throughout the south by 1900. H.P. Hammett pioneered this movement in South Carolina with the construction of the first and largest modern textile mill in South Carolina, Piedmont Manufacturing Company.

As stated before, after Hammett’s mill, more modern textile mills started popping up throughout the south in the 1880’s. While it began slow, southern textile mills became a force to reckon with for northern mills. As Table 2 indicates, by 1880 southern mills decreased their control to 5% of U.S. textile production. New England mills in 1880 saw their 1860’s control of U.S. textile production increase to 80.9%. But by 1890, southern textile production increased to 11% of the total U.S. textile market, while New England saw its first decrease of 5% loss of its U.S. market share coming in at 75.8% control U.S. textile production.

TABLE 2

In 1900, according to Table 3, southern textile industries again doubled their control of the textile market when they produced over 22% of the total textiles in the United States. On the other hand, by 1900, New England textile production suffered another decrease of national production when their numbers reduced from 75.8% of textiles produced in the U.S. in 1890, to 67.6% by 1900.

TABLE 3

NOTE: Table 3 Depicts “Mule” and “Frame” which are types of spindles.

In conclusion, while New England textile mills maintained a significant control of the total production of American textiles throughout the 19th century, by 1890 their control of the market was in a decade after decade decline until southern textiles industries surpassed them in production by the 1920’s. Advantages in labor and freight costs, access to waterpower and lower taxes mentioned before, were the primary reasons that led to southern mills eventual domination of the U.S. textile market.

Belcher, Ray. Greenville County, South Carolina: From Cotton Field to Textile Center of the World. Charleston: History Press, 2006.

Copeland, Melvin Thomas. “Cotton Manufacturing Industry of the United States”, Cambridge: Harvard University, 1912. #26 – The cotton manufacturing industry of the United States, by … – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library

United States Census Bureau. (1890) “Manufacturing Industries in the United States at the

Eleventh Census: 1890- Textiles.” 1890 census on production of manufactured goods.pdf

United States Census Bureau. (1900) “The Textile Industry of the United States.”

Volume 9. Manufactures, Part 3, Special Reports on Selected Industries (census.gov)

114 views0 commentsPost not marked as liked

Recent Posts

80Post not marked as liked

Piedmont’s YWCA Building and It’s History

Piedmont Manufacturing Company started spinning its spindles in 1876 after construction of the first mill building by owner

Henry P. Hammett: Greenville County Industrialist

Updated: 3 hours ago

In 1845, William Gregg wrote a series of essays in a Charlston newspaper, under the pen name, “South Carolina”. He wrote under this name to hide his identity, because what he said challenged the old Antebellum slave system. Gregg saw that slavery was coming to an end for the economically agrarian dependent south and a change was needed. Gregg argued the south needed to break away from its agrarian economy and develop its own industrial economy based on textile mills. He believed the south should no longer stand as a colonial economy to serve northern industries. Although Gregg presented strong arguments for an industrialized south, it mostly fell on deaf ears; slavery provided too much profit.

There were textile mills in the south a generation before Gregg’s essays, but these mills were not state-of-the-art compared to northern factories. Most lacked the required investment, operating with out-of-date dilapidated equipment that produced mostly yarn, which was sold to local markets. What Gregg called for was a true modern mill, built from the ground up, filled with the newest equipment, with operations overseen by skilled technical experts. While the south did not transform overnight as Gregg had hoped, a few that took notice of his speeches did.

Photo of Henry P. Hammett, Piedmont Historical Preservation Society Archives

One young textile producer in the late 1850’s, knew Gregg and heard his discussions on the economic capability of a modern southern textile mill. His name was H.P. Hammett, and he believed in Gregg’s theory, and began putting Gregg’s ideas in motion. Hammett, a partner in the Batesville Textile Mill, near Greenville, South Carolina worked with his partner, William Bates, on Gregg’s concept but life will derail their plan for a while.

Soon after the Civil War began, Hammett and Bates plans were derailed. Hammett was drafted into the Confederate Army, while William Bates operated his now confiscated mill that required him to produce material for the southern army. As the war went on and cotton became scarce Bates and Hammett sold their mill in 1863 and bought land on the Saluda River, about 15 miles east of their old location. They hoped to build a new modern mill on this site.

When the war ended, the southern infrastructure was a mess to say the least. In order to operate a successful mill, Hammett and Bates most importantly needed an efficient railroad, which they did not have. The Union destroyed the only rail line that connected Greenville to the market economy. This is the part in the story where Hammett will rise as a southern industrialist.

In 1866, Hammett was not only elected as a state representative, but he is also appointed as President of the Greenville-Columbia Railroad. His first responsibility is to fix the dilapidated/destroyed rail line connecting Greenville to Columbia, Southern Carolina. Without this functioning rail line connecting him to eastern markets, his textile business cannot exist. This rial line “coincidently” ran through the land Hammett and Bates purchased in 1863.

By 1870, Hammett not only has a well operating rail line, but built a depot in the rural countryside where his new mill was intended to be built. Hammett also used his political position to encourage the state to postpone taxes on new industries. Hammett is almost ready for his new mill, but fate would derail him again.

In the first few years of the 1870’s, Hammett served as the mayor of Greenville. In this position, he established business contacts and not only connected an east to west rail line to Greenville, but also a north south line connecting Greenville to New Orleans to the south and New York City to the north. But while Hammett used his networking skills to raise investment for his mill, William Bates dies and the Panic of 1873 hits. With this, many of his investors back out of his project. Not deterred though, Hammett goes on the road soliciting investment into his enterprise.

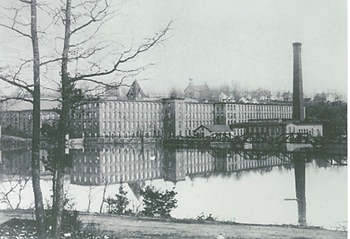

Photo of Piedmont Manufacturing Company, Piedmont Historical

Preservation Society Archives

By 1874, Hammett has sufficient capital to begin construction. The board of directors appointed Hammett as president and name the new business, Piedmont Manufacturing Company. By March of 1876, textile machines were turning in Hammett’s new mill. After the first six months, Hammett reports to his board of directors that the region’s first modern textile mill produced a 20% profit. His board of directors immediately offer more investment.

Unlike other industrialist of the time, Hammett did not keep his successes a secret or try to take over his competition. He publicly promoted the success of his mill, instructing others on the financial windfall that could benefit any southern men who ventured to build their own textile mill. Hammett, like Gregg, saw the successes of his mill as the future for the south’s recovery after the war, as a way that his section could stand tall on a national level with the rest of the country.

Child Labor in the Southern Textile Mills: Survival, Reform, and Memory

Child labor in the Southern textile mills has long stirred debate among reformers, journalists, and historians. Was it simply exploitation, a symbol of the South’s backwardness? Or was it a strategy of survival for families trying to make ends meet in mill villages? The reality was complex. For mill families, children’s work was often essential, while outsiders, especially Northern reformers, condemned the practice as immoral. This essay argues that child labor endured not because Southerners rejected modern ideas of childhood, but because it was woven into the economic and cultural fabric of mill village life.

When mills sprang up across the South in the late nineteenth century, boosters promised that industrial jobs would modernize the region. Families moved from farms into mill villages, drawn by the promise of steady wages and housing. But mill pay was low, and rent and groceries, often sold through company stores, could consume much of a household’s income. In this setting, children’s wages were not optional. As historian Daniel Holleran shows, in some Piedmont families, children brought in as much as a third of the family’s total earnings.1

Mill villages reinforced this dependence. Families rented mill-owned houses and relied on company-controlled amenities. Falling behind on bills could mean eviction. Historian Thomas Dublin has argued that these circumstances blurred the line between necessity and exploitation: children’s labor propped up the household economy, but it also tied entire families more tightly to the company.2 For parents, sending children into the mill was a painful calculation, but often one of survival.

To Northern reformers, however, child labor symbolized Southern backwardness. Organizations like the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) distributed pamphlets and Lewis Hine’s famous photographs of weary mill children. Activists such as Alexander J. McKelway warned that long hours and dangerous machinery robbed children of education, health, and morality.3 For them, child labor was not just a regional issue but a national stain.

Unions and Northern manufacturers also had practical motives.

They worried that cheap Southern textiles, produced in part by child labor, undercut their competitive position. Historians Daniel Holleran and Walter Trattner have noted that calls for federal child labor laws reflected both humanitarian and economic concerns.4 Condemning the South thus served moral and market purposes.

But these critiques often ignored the realities of Southern mill families. As Elizabeth Fones-Wolf has pointed out, reformers rarely asked what alternatives poor families had. Agricultural wages were low, local schools were underfunded, and opportunities for advancement were scarce.5 Condemnation alone did little to change those facts.

Southerners often pushed back against outside criticism. Local newspapers insisted that Northern reformers misunderstood the South. Parents argued that without their children’s wages, families would fall into destitution. Some even suggested that mill work was better than field labor was safer, cleaner, and more likely to lead to advancement within the mill system.6

The cultural gap was wide. Reformers envisioned childhood as a protected stage of life. In mill villages, children had long been part of the family economy, first on farms and then in factories. Historian Mary Frederickson has shown that in Southern culture, children were expected to contribute early, making mill work feel like a continuation of tradition rather than a betrayal of it.7

Even after reformers won child labor laws, enforcement was weak. Inspectors were few, and families often lied about children’s ages. Mill owners, facing labor shortages, looked the other way. Early national laws, such as the Keating–Owen Act of 1916, were struck down by the Supreme Court. Not until the 1930s, with the Fair Labor Standards Act, did child labor decline in practice.8

Historians, like reformers, first tended to describe mill child labor mainly as exploitation. Later labor historians echoed this perspective, presenting child labor as a byproduct of capitalist greed. By the 1980s, however, scholarship began to shift. David Carlton’s Mill and Town in South Carolina (1982) and Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s Like a Family (1987) emphasized how family economies shaped mill life. They acknowledged exploitation but also stressed that families were making hard choices in difficult circumstances. Timothy Minchin later argued that reform campaigns without economic alternatives often made families even more vulnerable.9

More recently, scholars such as Grace Hale and Joe Crespino have pushed the conversation further, exploring how child labor intersected with race, gender, and Southern identity. Reformers’ attacks on Southern mills, they argue, reinforced cultural stereotypes about the South as poor, white, and morally deficient.10 In this light, child labor was not just an economic practice but also a cultural marker—used by outsiders to define and stigmatize the region.

Child labor in Southern textile mills was a survival strategy. Northern reformers condemned it as exploitation, while Southern families saw it as a necessity of life in mill villages. The paternalistic system of housing, wages, and company stores and the families desire for economic improvement resulted in families choosing to send children to work. Reformers’ campaigns succeeded in raising awareness but faltered because they offered no realistic alternatives until broader changes came in the twentieth century.

The historiography has moved from moral judgment toward contextualization. Today, historians recognize both the suffering of children and the resilience of families who endured. To reduce the story to exploitation alone oversimplifies the lived experience; to excuse it entirely erases the costs paid by children. The history of child labor in the Southern mills reminds us, that nation-building was partially borne by the youngest members of society.

Footnotes

1. Daniel A. Holleran, Textile Families: Mill Work and Household Economy in the New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 87–90.

2. Thomas Dublin, Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826–1860 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979), 45–47.

3. Alexander J. McKelway, “Child Labor in the Carolinas,” National Child Labor Committee Pamphlet No. 1 (1909); Lewis Hine, Child Labor in the Carolinas: Photographs and Reports (New York: NCLC, 1910).

4. Daniel A. Holleran, Textile Families, 122; Walter I. Trattner, Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America (Chicago: Quadrangle, 1970), 56.

5. Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Selling Free Enterprise: The Business Assault on Labor and Liberalism, 1945–60 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 11–13.

6. “Mill Life Defended,” Greenville News, July 7, 1908.

7. Mary Frederickson, Between Mothers and Daughters: The Making of Female Culture in the South, 1865–1915 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 88.

8. Walter I. Trattner, Crusade for the Children, 183–85.

9. Thomas R. Dawley, The Child That Toileth Not: The Story of a Government Investigation That Was Suppressed (New York: Thomas R. Dawley, 1912).

10. David Carlton, Mill and Town in South Carolina, 1880–1920 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982); Jacquelyn Dowd Hall et al., Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987); Timothy J. Minchin, Fighting Against the Odds: A History of Southern Labor Since World War II (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005).

11. Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (New York: Pantheon, 1998); Joe Crespino, In Search of Another Country: Mississippi and the Conservative Counterrevolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).